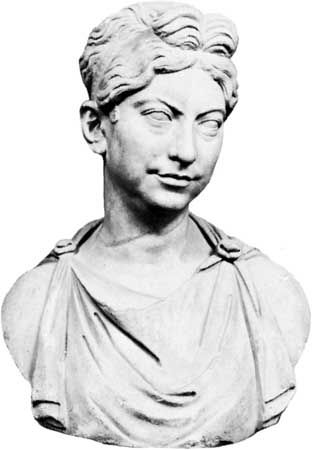

Born c. 235 CE, her native Palmyrene name was Bat-Zabbai (written “Btzby” in the Palmyrene alphabet, an Aramaic name meaning “daughter of Zabbai”). Palmyra (modern-day Syria), which the ancients also knew as Tadmor or the “city of the palms,” was a bustling city-state which at least theoretically had been incorporated into the Syrian province of the Roman Empire about 114 CE under the Roman emperor Hadrian. The Romans allowed the Palmyrenes considerable freedom within the imperial structure. They collected their own taxes, and by the turn of the 3rd Century they elected their own senators who governed Palmyra under the Roman banner. In turn, the city-state recruited highly skilled archers who helped defend the elastic Roman frontier against the Parthian Empire in the east. Palmyra had an extensive trade network, and was at the time a sophisticated international city of wealth.

Bat Zabbai came from a privileged background. She was Arab, but claimed through her father Amru to be related to the Macedonian Ptolemaic monarchs of Egypt which included the fabled Cleopatra. Zabbai was well educated, having been tutored by a famous Greek, Cassius Longinus, whom she later kept as part of her court as both a teacher and a conversationalist. Further, she patronized Neoplatonist philosophers and compiled an epitome of the works of Homer and other renowned historians. She herself wrote a history of Palmyra, being literate at a time when writing was unknown to most people. Reputedly, she knew the Greek, Syriac, and Egyptian languages equally well and understood some Latin.

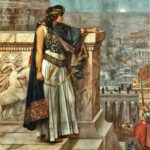

In the late 250s, Bat Zabbai married Odainat (Odenathus), a Syrian noble who was named consul of Palmyra in 258 CE. They were well matched, both ambitious and both raised to the toughness of the desert bedouins. They hunted, rode and camped in the wilds together, Bat Zabbai riding astride her stallion rather than in a more comfortable chariot. Present in the thick of a fight, she delighted in wearing armor and accompanying her husband on forays against their enemies.

When the Roman Emperor Valerian was murdered by Sapor I of Persia, Odainat had the diplomatic excuse he needed to expand Palmyra by attacking the Persians. Bat Zabbai commanded the army that laid siege to Sapor, and the couple overcame the Persians. They then turned west and won several victories that added sizable domains to the Palmyran city-state.

In 266/7 CE, the king and his heir (from a previous marriage) died under suspicious circumstances, and Queen Bat Zabbai assumed control of the Palmyran Empire, acting as regent for her young son Wahballat (called Vaballathus in Latin, Athenodorus in Greek). She immediately launched military campaigns of further conquest. In 269 CE, Egypt fell to her, and then she annexed what remained of Syria. In a few years under her leadership, her rule extended from Egypt to the Bosporus, and from the Mediterranean to India. After her troops took Antioch and eastern Anatolia, she made military alliances with Persia, Arabia and Armenia. She was in effect ruler of the eastern Roman empire, and declared herself independent of Rome, new controller of the Roman trade routes through the Arabian peninsula and the Near East.

She struck coins in her likeness, a particular snub to Rome, and spent lavishly to raise her court to the opulence of her hero and claimed ancestor Cleopatra. She also made her court a center for intellectuals, philosophers, scholars and artists of all kinds. Her ambition was to control the entire Roman empire and she even had a chariot of gold made for her victorious entrance into Rome. But at the end of 270 CE, Aurelius was crowned Roman emperor, and he was determined to take back all that had been lost. In 272, Aurelian’s army crossed the Bosporus.

He retook Egypt and moved on Ankara. Queen Zabbai staged her first direct engagement with the Romans in the Taurusian wilds outside Ankara. In a rearguard action, she hoped to cover the retreat of the main body of her forces north to Emesa, and she faced Aurelian with a line of Palmyran archers, the most feared in the East, flanked with infantry and heavy cavalry. The Romans were pushed back by Zabbai, who was regularly seen riding among her troops and communicating her commands through her general Zabdas.

The Palmyran cavalry charged the Roman lines, which broke before them. Losing discipline in what they thought was a rout, the cavalry pursued only to be drawn into a trap in which their support from the archers and infantry in the rear was severed. Aurelian regrouped his soldiers and slaughtered the Palmyran forces.

Queen Zabbai fell back to Emesa and prepared to defend the town, urging her men to stand strong as she rode among them in her battle armor, but Aurelian’s legions once more outfoxed the Palmyran cavalry. The Queen wrote a letter to Aurelian after this battle in which she boasted, “I have suffered no great loss, for almost all who have fallen were Romans.” She referred to the fragments of the Roman legions, once garrisoned in Palmyra, who had earlier joined her army.

Within days of the battle at Emesa, Queen Zabbai led a retreat through several hundred miles of desert as her armies withdrew to the stronghold of Palmyra for their last effort against the Romans. Aurelian’s war on the Palmyran queen was proving costly in time and lives. As he maneuvered through the unfamiliar desert, she sent her mounted archers, Parthian fashion to pick away at the advancing legions. Thus impeded, he could not catch the Queen before she attained her stronghold and prepared for the siege she knew was coming. She stripped the mausoleums outside the city of marble and granite to augment the walls of Palmyra and sent her ambassadors to neighboring kingdoms to request assistance.

On Aurelian’s first charge against the walls of Palmyra, he was wounded by a Palmyran arrow. The wound, coupled with the news that the senators in Rome were questioning why the great Emperor Aurelian was having such difficult fighting a woman, stirred him to write a famous letter, a testimony in to the martial prowess of Bat Zabbai. He addressed the senate:

“The Roman people speak with contempt of the war I am waging against a woman. They are ignorant both of the character and the power of Zenobia. It is impossible to enumerate her warlike preparations of stones, of arrows, and every species of missile weapons. Every part of the walls is protected with two or three balistae, and artificial fires are thrown from their military engines. The fear of punishment has armed her with a desperate courage.”

Aurelian had understood the military competence of Bat Zabbbai and brought with him the best of his legions and commanders. Still, the price she was forcing him to pay was seriously impacting his campaign. Rather than face her for many more months, he offered her generous surrender terms. She wrote in reply:

“It is not by writing, but by arms, that the submission you require from me can be obtained. You have dared to propose my surrender to your prowess. You forget that Cleopatra preferred death to servitude. The Saracens, the Persians, and the Armenians are marching to my aid; and how are you to resist our united forces, you who have been more than once scared by the plundering Arabs of the desert? When you shall see me march at the head of my allies, you will not repeat an insolent proposition, as though you were already my conqueror and master.”

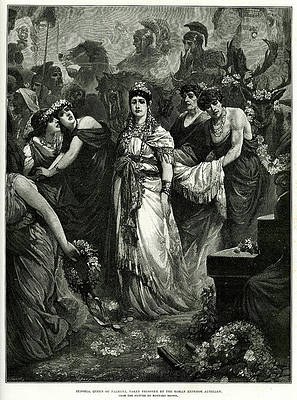

Finally Queen Zabbai, realizing that Palmyra would be lost, mounted her fastest camel and with a small retinue retreated 60 miles across the desert to the Euphrates, where she hoped to find a boat that could take her eastward into the lands of her allies. She was captured on the river bank and returned to Aurelian, who transported her to Rome to march in his triumphal procession.

The parade in 273 CE presented to the Roman people 20 elephants, four Bengal tigers, several hundred exotic animals, ambassadors in their native dress, thousands of war captives (including a group of Goth women identified as Amazons), 1,600 gladiators who would later take part in ceremonial games, and kings, queens, generals and warrior elites whom Aurelian had bested in his reconquest of the Eastern Empire. Each captive bore a plaque around their neck identifying them for the populace. Zenobia was spared such indignity, as it was assumed that everyone would know who she was. She was so heavily weighed down with her famous gold and jewels that she required a slave to help her walk. As a final mockery, the golden chariot in which she had planned to enter Rome victorious, followed behind her, riderless.

Queen Bat Zabbai, called by the Romans Septima Zenobia, lived the remainder of her life in grand style, albeit a captive of Rome. Her fame and wit gained her the sympathy of a number of Roman senators, including one who married her and gave her a villa near the present-day city of Tivoli. Her salons, with the literati of the day in attendance, became a principal feature of Roman cultural life.

excerpted from David E Jones, “Women Warriors” ISBN# 1-57488-106-X